I strongly identify as a mixed-race Black and Latina female. I was raised by my parents to never choose just one or the other because I am both: all day, everyday. As passionately as I hold my racial/ethnic identity to be true, I have grappled with the fact that the world sees my truth as a falsity. I, Joanna Lillian Thompson, am proud to say I am the child of a Black man, born and raised on the ghetto streets of southeast Washington D.C., and a Central American woman from Nicaragua who came to the United States with nothing but a dream for a better life.

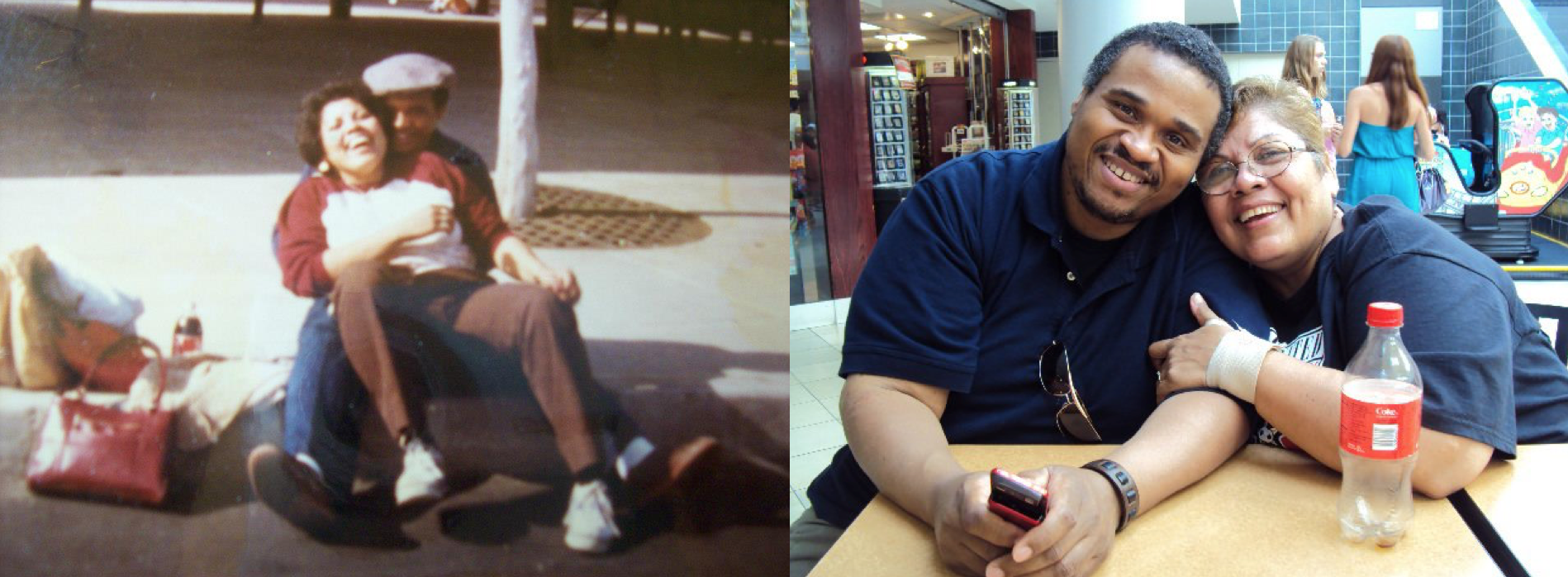

Left: My parents during their courtship in the 1980’s; Right: My parents a few years ago during a visit to Chicago.

As a child, being mixed was not complicated. I grew up in the rather diverse suburb of Rockville, Maryland, right outside of the nation’s capital. There, commonalities between my friends and neighbors were highlighted more so than our differences. However, as I have gotten older and moved away from home to travel nationally and internationally to pursue my academic and career goals, I have found myself in more and more situations where my mixedness becomes a topic of interrogation. These situations are fueled by constant reminders of what makes me different from those who do not identify as mixed-race. Unfortunately, I am more than used to typical questions of “What are you?” or “What are you mixed with?” and statements like, “I didn’t think being mixed was a thing.” or “You don’t even seem Black and Latina.” Nevertheless, the questioning of my racial/ethnic identity has come to a point where it is not just a question of what am I, but a discrediting of my racial/ethnic identity all together.

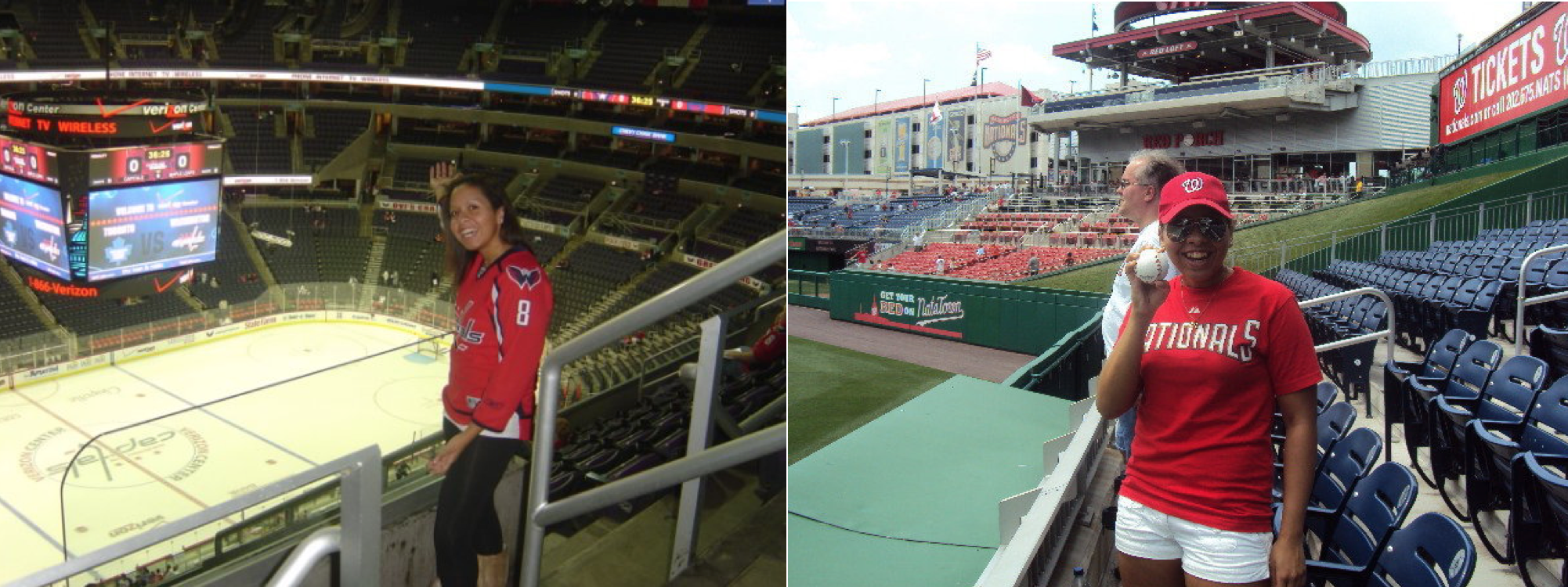

This discrediting of my racial/ethnic identity recently came to a highpoint when a new friend of mine, who is Black and undeniably Pro-Black in her personal beliefs, frankly informed me that I am not “ethnic,” I have been “whitewashed” because it sounds like I was “sheltered,” like my parents “kept all the Black people” away from me, and I am “not like any other Black/Latina person” she knows because “other Black girls” don’t sound like how I do. The justification for my apparent display of no ethnicity, according to my friend, are due to characteristics I embody such as I am passive and am too nice, I talk properly all the time, I like baseball and hockey, I do not listen to a lot of “Black people” music, I am not urban, I say phrases like “okie dokie,” and I simply carry myself in a way that if you did not know me, you would not necessarily think I was Black or Latina. These characteristics, from how I act, to how I speak, to even what sports and music I like, have somehow, and unbeknownst to me, stripped away my racial/ethnic background. Ultimately, it has made me a White person.

Left: Me in my Alexander Ovechkin jersey at a Washington Capitals game; Right: Me after catching a ball from a pitcher during batting practice at a Washington Nationals game.

When thinking about these characteristics, which seem to be perfect evidence to support the claim I am not “ethnic,” I believe what I like and how I act are merely consequences of the environment I was raised in and the spaces I continue to surround myself in. I was raised in Montgomery County, Maryland, which was a well-off suburb. Compared to most youth, I had a pretty amazing childhood which included an abundance of love from friends and family who were prosperous themselves. I do not say that to be conceited, but to simply acknowledge the varying levels of privilege I have been given in my life. My childhood included being excited for my first Backstreet Boys concert at the age of 13; yearly summer vacations to the beaches of Florida with my parents; attending different professional sports events, including soccer, because my father, that Black kid from the ghetto of D.C., worked as an equipment manager for the Washington Diplomats in the 70’s and fell in love with the sport, among other sports as well. My life includes both of my parents, whom have now been married for 34 years, and have always supported me in any way they can: financially, emotionally, spiritually, and just by being my best friends. Today, I live on the north side of Chicago where I am pursuing my PhD in Criminology, Law, and Justice at the University of Illinois at Chicago and have been extremely fortunate to meet people from different walks of life who are just as diverse as I am. Somehow, these wonderful characteristics, which have irrefutably shaped the eclectic person I am today, have simultaneously disqualified me from being genuinely Black and Latina.

Me as a child in Maryland

Left: Senior yearbook photo; Right: High school graduation

Left: My parents and I at a Washington Redskins v. Detroit Lions football game in Detroit, Michigan; Right: My parents and I at dinner the day I graduated from college at West Virginia University.

Several questions have since risen in my mind from this new information on my lack of minority status. First, what does it mean to be ethnic? Second, what does it mean to be “genuinely” Black and/or Latina? Third, how does having a nice personality, liking certain types of music and sports, or being well-spoken as a POC essentially make you less of a POC? Sometimes I wonder, if I were to give into stereotypes, would that make me more genuine when it comes to my racial/ethnic identity? If I grew up on the same ghetto streets as my dad, if I struggled in the shacks of Nicaragua like my mom, if I had not been afforded good opportunities in the affluent suburb I grew up in, if I had a single parent to support me and wondered why one parent left, if I carried myself with a heavier and more aggressive swagger, if I blasted ratchet music 24/7 and spoke with more street slang, if I asserted a more visible pro Black/pro Latina way about myself, would all of that somehow qualify me as ethnic, would all of that somehow make me a bonafide Black and Latina female?

Personally, I cannot deny that I have struggled with questions of, “Am I enough?” and “Will I ever be enough?” This is because I have been, and most likely always will be, reminded that as “half and half,” I will never be fully Black or fully Latina. Yes, I could feel as whole as I wanted, I could shout it from every mountaintop and be proud of the reality I hold to be true, but the world will always see me as two parts of a whole, never two whole parts. The saddest part about these reminders is they usually come from my own people: Blacks and Latinas/os. My own people, who I assume will be the first to have my back in times when I am feeling inadequate, are the first to criticize and remind me that ultimately, I am neither Black or Latina.

And so, what happens now? Where do mixed-race individuals like myself, who are constantly being reminded of what we are not rather than what we are, go from here? Do we stop believing in who we are, whether our racial/ethnic identities are perceived by others correctly or not? Do we continue to convince our own people, the ones who give us the most pushback for not being enough that yes, we are enough and we should not be stripped of our racial/ethnic identity simply because we look different, sound different, or prefer to engage in different cultural interests? Do we try and establish definite connections for what it means to be “ethnic” or “genuine” as a POC so that at least we have “rules” to abide by when claiming a minority racial/ethnic identity? Or do we just not care, let the sensitivity and emotion all slide, and just deal with being accepted by some and not by others?

At the end of the day, I know I cannot give into the negative feelings I experience from discontent and questioning by others who feel I am inaccurately portraying the racial/ethnic identity I was born into. I know I cannot change people’s opinions, especially if those opinions are not grounded in anything definitive, anything aside from personal ideals. I also know the pride I have in my claim as a Black and Latina female is my truth, my reality, and that will never falter. Despite potentially not fitting into whatever cookie-cutter mold there is for being a “genuine” POC, best believe, no one can tell me that I do not fit into the history of what it means to be Black and Latina in America, because I do, I know I do. My place in history, as a strong Black and Latina, has been written and continues to be written; backed by a soundtrack of pop and hip-hop, a wardrobe of sneakers and sun-dresses, hooping to the basket on the court and sliding into third on the field, a personality that is equally passive and aggressive, and a swagger that is undeniably a lady in the workplace and a beast in the streets. Whether this depiction of who I am is evident to others or not, I know is it there. It is in my being, it is in my blood, it what wakes me up every day and puts me to sleep every night. And you know what? That will always be enough for me.